Reading about NIMBY complaints to increased building heights in Glaeser’s skyscraper article reminded me of an ongoing dispute in my own neighborhood. Late last year Brooks Running announced it would be moving its corporate headquarters to the corner of Stone Way and 34th on the boarder of Wallingford and Fremont. The project is a being developed by Skanska and is participating in the City of Seattle’s Living Building Challenge Pilot Program.

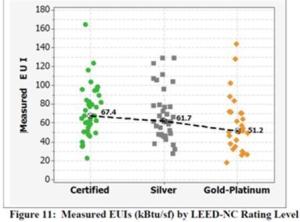

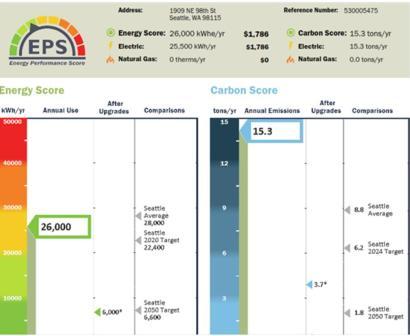

Low-impact development, density, 300 new jobs, all sounds pretty good right? Not if you talk to some of my neighbors opposing the project. The major complaint is that Skanska is seeking an exemption to the 45ft height limit in the area. By achieving a 75% reduction in energy use, the project is asking for an additional 20ft to add a 5th story and make their Proforma pencil out.

What I find ridiculous about this dispute, is that the best argument community members can come up with is that the building’s height will look “out of place”. This is amusing when you look at the section drawing below showing the proposed height of the Skanska project (center) in relation to current and potential 45ft neighbors. Calling this project out of place is a more than a stretch, especially when looking at the potential height of adjacent buildings.

As a nearby resident I love the idea of this underused corner being developed. To me this development means more patrons for the small local shops in the area, more demands for housing, and could serve as a catalyst for the entire area. Fremont/Wallingford is an ideal location to foster sustainable development that increases density in what is already a walking and transit friendly neighborhood. There will always be community members opposed to any kind of change, but a applaud Mayor McGinn for championing this project, and I hope it moves forward.